Contents

- Summary

- What is Male Disposability?

- Study on Moral Choice

- Overtaking Study

- Helping Behaviour

- Causes

- Where do these attitudes come from?

- Conclusion

- Updates

Male Disposability – The Evidence

Summary

Numerous studies show that people are more willing to inflict harm on men than women, more willing to kill men than women, and treat harm against men as less serious than harm against women. Women treat men as less valuable to a greater degree than men, and women who identify as feminists may be even more sexist than women on average. These attitudes are promoted by women to their children, but not by men.

What is Male Disposability?

Male disposability means the tendency to treat men and boys as disposable compared to women and girls, for example treating the death of men as less serious than the death of women.

Study on Moral Choice

An exhaustive research project involving multiple studies by a team of psychology researchers at New York University has found overwhelming evidence for male disposability

[1]

Abstract:

Moral perceptions of harm and fairness are instrumental in guiding how an individual navigates moral challenges. Classic research documents that the gender of a target can affect how people deploy these perceptions of harm and fairness. Across multiple studies, we explore the effect of an individual’s moral orientations (their considerations of harm and justice) and a target’s gender on altruistic behavior. Results reveal that a target’s gender can bias one’s readiness to engage in harmful actions and that a decider’s considerations of harm—but not fairness concerns—modulate costly altruism. Together, these data illustrate that moral choices are conditional on the social nature of the moral dyad: Even under the same moral constraints, a target’s gender and a decider’s gender can shift an individual’s choice to be more or less altruistic, suggesting that gender bias and harm considerations play a significant role in moral cognition.

Despite the careful phrasing of the abstract to avoid mentioning exactly which gender the “gender bias” is against, in fact every study shows that participants are more willing to harm men than women.

This includes the following studies:

Trolley Problem Study

First the researchers used the classic trolley dilemma, this involves a hypothetical situation where the subjects have to choose whether to push a bystander off a footbridge onto a track in order to save other people from being hit by a trolley.

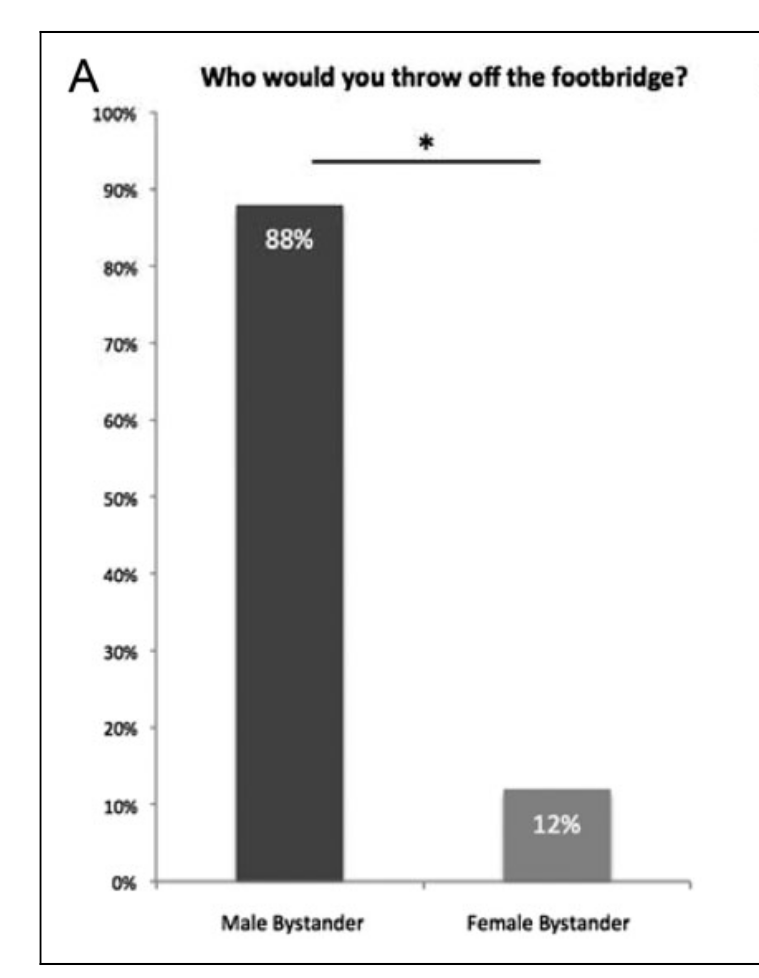

First they varied this problem by giving the subjects an option of pushing either a man or woman off the bridge, the result:

In Study 1A, 88% of participants reported that they would push the man off the footbridge (Pearson’s w 2 1⁄4 28.88, 1 df, p < .001, Z 2 1⁄4 .57; Figure 1A), illustrating that participants significantly endorsed the preservation of a female over a male bystander’s welfare

The result is highly statistically significant, with the probability the results are due to randomness being less than one chance in a thousand.

To confirm this result, another variation was run. In this study they gave some subjects a dilemma involving killing a male bystander, and some involving a female bystander.

Participants in Study 1B were randomly selected to read one of the three versions of the dilemma, where each vignette described a man, woman, or gender-neutral bystander on the bridge. The participant was then asked how willing they were to ‘‘push the [man/woman/person] onto the path of the oncoming trolley,’’ indicating on a 10-point analogue scale willingness to push (WTP). The aim was to determine whether there are observable gender biases during philosophical moral dilemmas, with the key variable being how readily a male or female bystander is pushed onto the tracks (i.e., harmed).

In this case, they also recorded the participants gender. Again, this found a highly significant bias against men among female participants.

Results revealed a main effect of the bystander’s gender, F(2,146) 1⁄4 3.8, p 1⁄4 .02, Z 2 1⁄4 .05 (Figure 1B), such that participants were overall more willing to push a man (mean WTP 1⁄4 3.3, SD + 2.4, 10 1⁄4 very willing) or a bystander with an unspecified gender (mean WTP 1⁄4 4.3, SD + 3.1) than a woman (mean WTP 1⁄4 3.0, SD + 2.4).

Together, this reveals that participants were less willing to push a woman than a man off the footbridge, suggesting that even within the hypothetical domain where the tensions are not as easily simulated (FeldmanHall et al., 2012), individuals take a target’s gender into account when contemplating harmful actions.

Shock Study

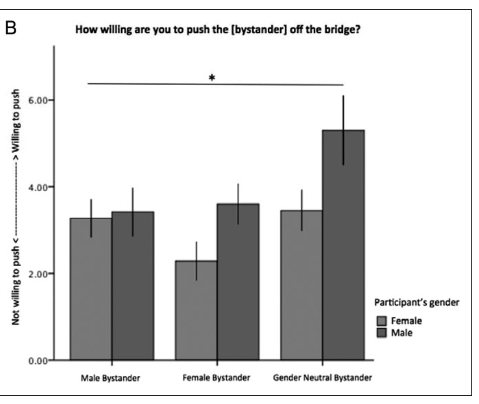

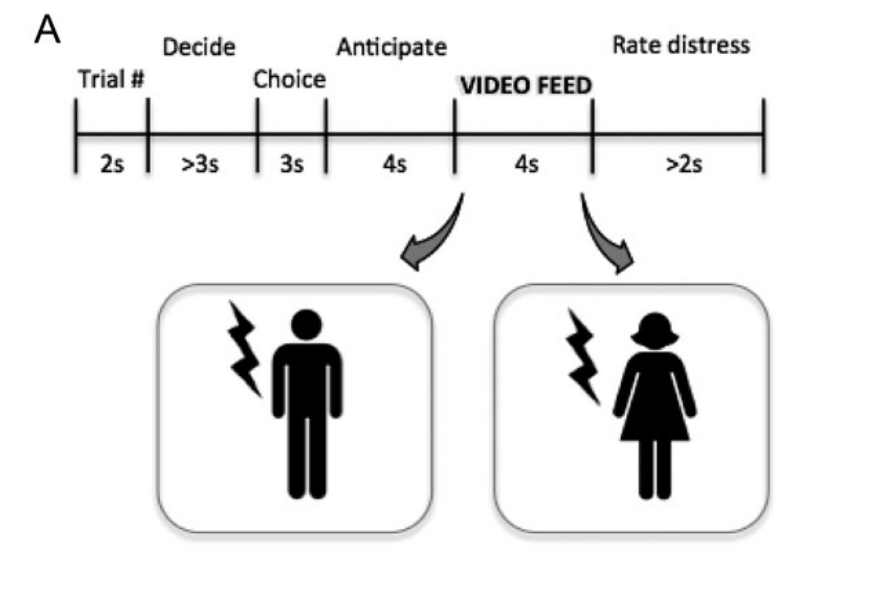

While the above studies measure peoples willingness to kill men vs women, the researchers also studied willingness to hurt people without killing them.

This was measured with an experiment where participants would receive money in return for allowing a target to receive electric shocks. In fact the target was a confederate of the researchers and pre-recorded videos were shown of people being shocked instead of a live feed. This is similar to the notorious Milgram experiment.

The design was such that participants could save money by allowing the target to get a shock:

On each trial, £1 was at stake, and the choice was how much, if any, of the £1 to give up in order to prevent a painful but harmless electric shock from reaching the target on that trial. The more money paid out on a given trial, the lower the shock level inflicted on the target…Paying the full £1 would remove the shock altogether, while paying nothing would mean the target experienced the highest shock level on that trial. The key behavioral variable was how much money (£0–£20) deciders retained across the 20 trials, with larger amounts indicating that personal gain was prioritized over the target’s pain. Effectively, the more money the decider paid, the lower the shock level the target received on a given trial.

Again, the researchers manipulated the gender of the target to control how willing subjects were to shock either sex.

Deciders were also required to view the administration of the shocks. This allowed us to manipulate the target’s gender by broadcasting a video of either a male target (Condition 1) or female target (Condition 2) responding to the shock

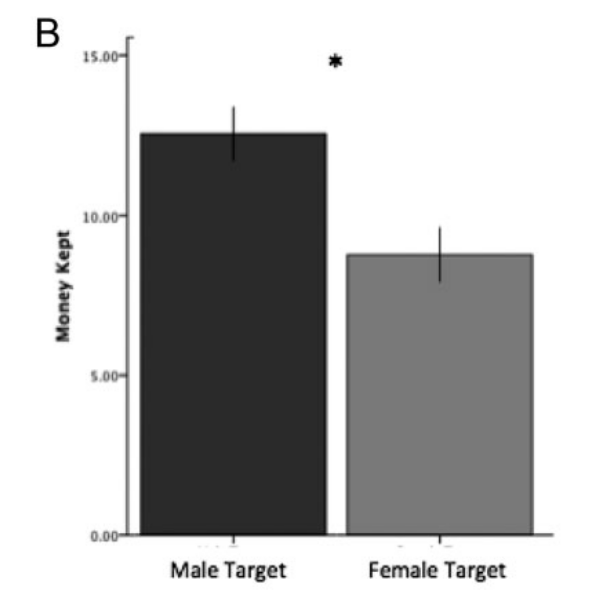

The results showed people want less money to shock men than women

deciders interacting with a female target kept significantly less money and thus gave significantly lower shocks (n 1⁄4 34; £8.76/£20, SD + 5.0) than deciders interacting with a male target, n 1⁄4 23; £12.54/£20, SD + 3.9; independent samples t-test: t(55) 1⁄4 3.16, p 1⁄4 .003, Cohen’s d 1⁄4 .82; Figure 2B. This replicates the findings from Studies 1A and 1B in the real domain and under a different class of moral challenge, illustrating that harm endorsement is attenuated for female targets. Together, this suggests that a target’s gender can powerfully shift the perception of harm and lead to an increase in costly altruism

My emphasis

Overtaking Study

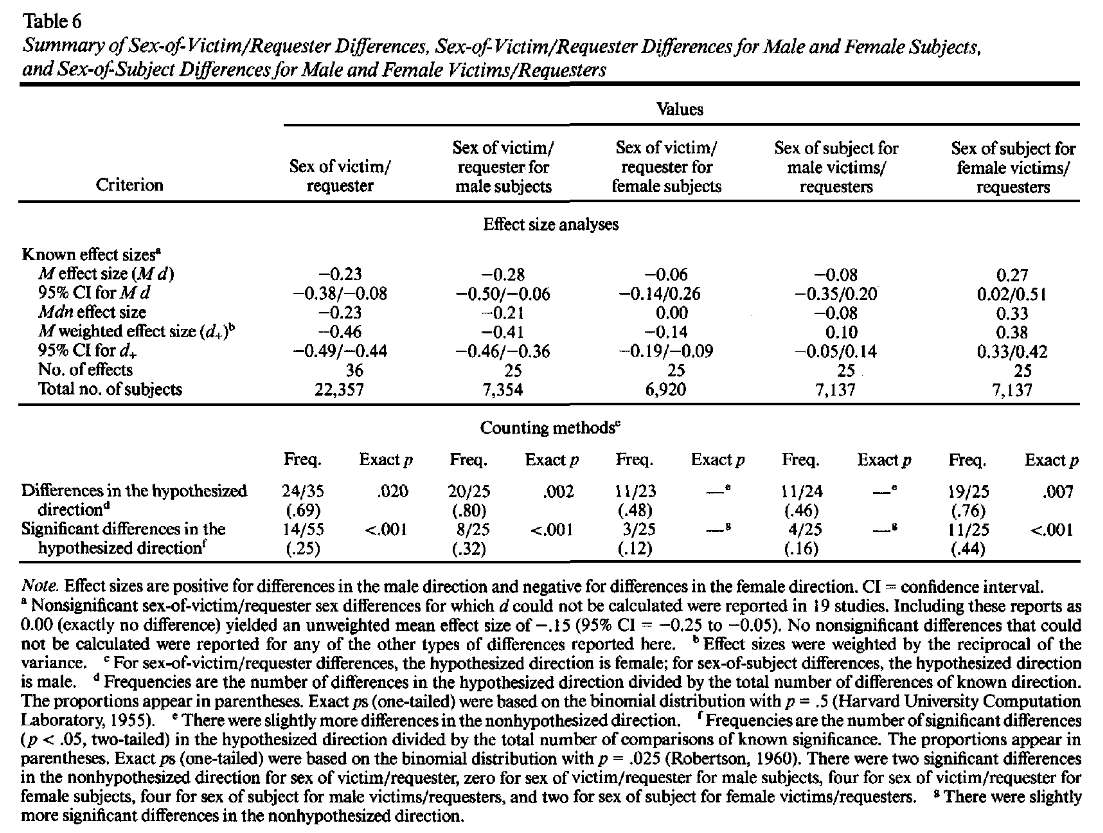

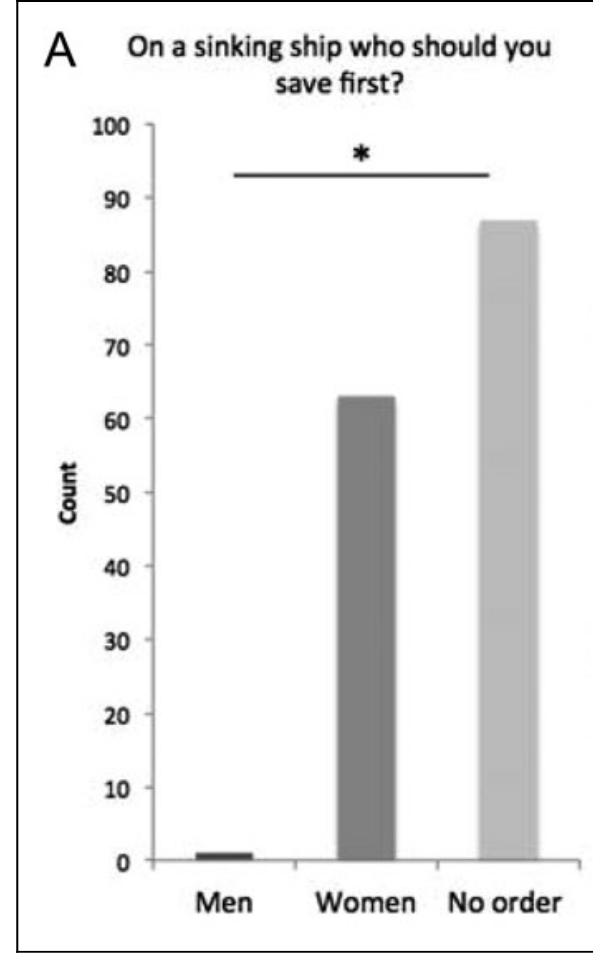

This applies to real-world behaviour as well, a study on drivers overtaking cyclists showed that drivers passed significantly closer to female cyclists than male.

On average motorists left considerably more space when passing the rider when he gave the impression of being female. A two-tailed independent-samplest-test confirmed that the effect was significant (t279= 3.71,p< .001,d= 0.44). The difference in means is over 14 cm … drivers left more space for what they thought was a woman [2]

Helping Behaviour

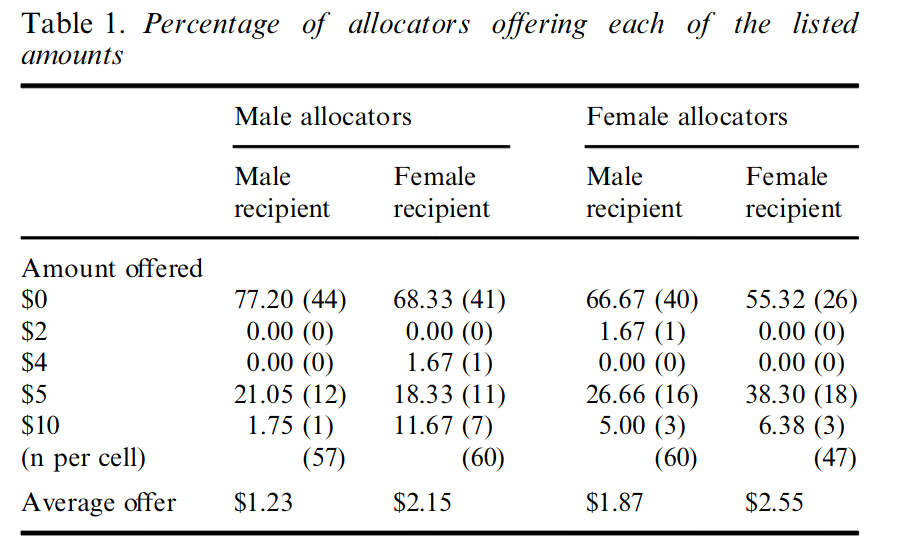

Bias against men doesn’t just apply to the amount of harm, but also the amount of help people give to men and women.

A paper published in the Psychological Bulletin reviewed over 172 studies examining behaviour towards people requesting help with an aggregate total of 22,357 subjects. It found women typically receive more help than men

[3]

to a statistically significant effect (less than 1 chance in 1000 due to randomness)

The means of the effect sizes deviated from 0.00 in the direction of greater helping received by women than men … all of the mean differences were in the female direction (negative numbers) and, as shown by their confidence intervals, differed significantly from 0.00, thus indicating a significant difference.

Interestingly this sexism was larger when subjects believed they were being watched, suggesting that this is the result of social pressure not intrinsic instinct.

Consistent with these significant effects, the tendency for women to be helped more than men was stronger (a) in off-campus settings versus campus settings (field and laboratory); (b) with surveillance versus unclear surveillance, x2(2) = 221.18, p < .001, and unclear surveillance versus no surveillance, xz(2) = 39.28, p <.001…The tendency for women to be helped more than men was larger if the helper was under surveillance by persons other than the victim or requester.Surveillance by onlookers emerged as by far the strongest predictor of the sex-of-victim/requester effects

This is confirmed by a study published in Applied Economics Letters, using a game in which subjects can choose to altruistically share money with other players. Both men and women gave more money to women than men

[4]

Causes

The researchers in the “Moral Chivalry” study next attempted to find the root cause of male disposability.

Possible causes being that people have an instinctive greater emotional reaction to hurting women, or that people are responding to societal norms of how acceptable violence is against men.

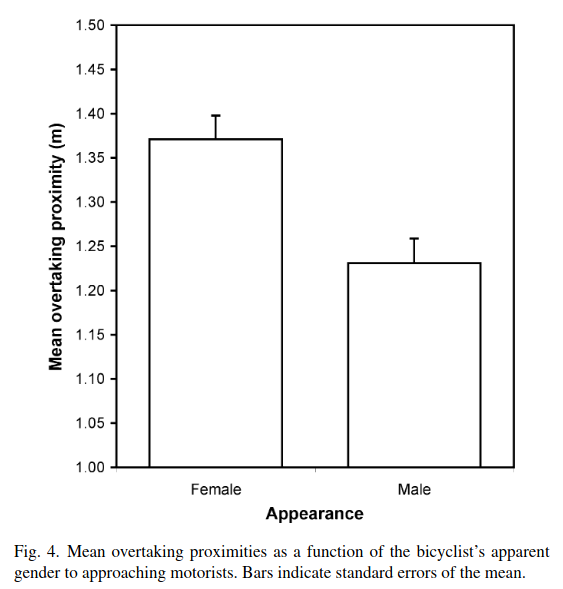

To test the possibility that male disposability is caused by social norms, they asked about who should be saved first on a sinking ship. In this case it is widely known that the social standard is “women and children first”, so if social expectations played a role the bias would be greater here.

only one participant reported that men should be saved first (Pearson’s w 2 1⁄4 78.3, 2 df, p < .001, Z 2 1⁄4 .52), and the rest of participants responded that there should either be no order or that women should be saved first (Figure 3A)

Again, this is highly statistically significant.

Then subjects were presented with the studies tested above as hypothetical scientific studies, and asked how they thought participants would act. The subjects correctly predicted people would be more willing to harm men (consistent with this being a social norm)

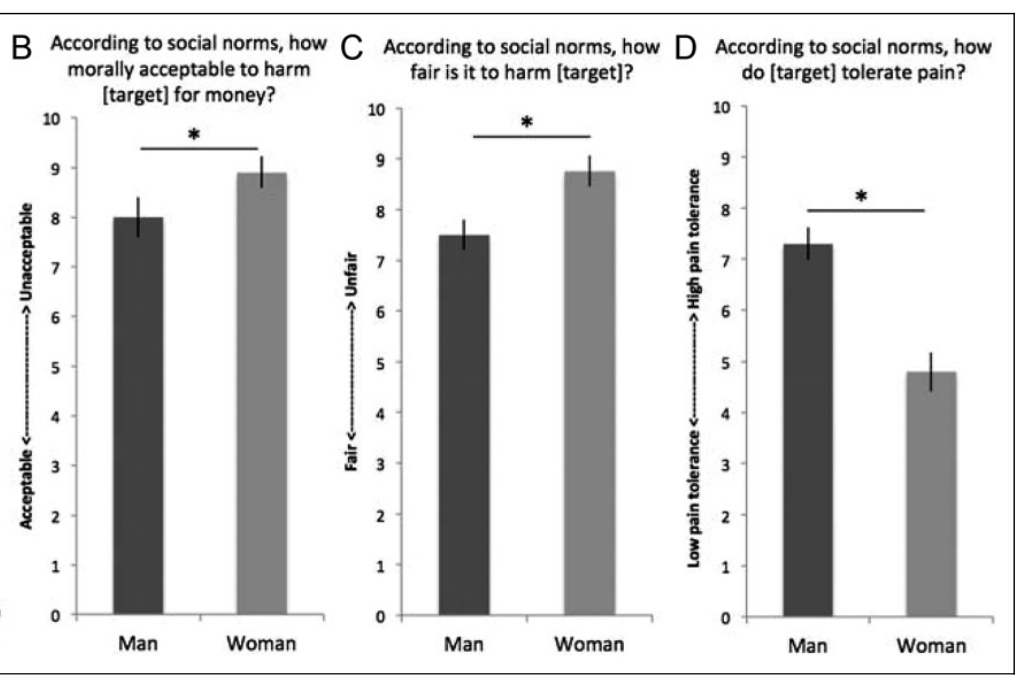

They were also asked how acceptable it is to harm a man vs a woman and consistently said that it is more acceptable to hurt men.

participants in Study 3A reported most volunteers would keep significantly less money when engaging with a female than a male or gender-neutral target … harming females was perceived as significantly more unfair than harming either a man or a gender-neutral person

we observed that according to social norms, it is significantly (1) more morally unacceptable to harm a female for money, paired samples t-test: t(49) 1⁄4 2.6, p 1⁄4 .01, Cohen’s d 1⁄4 .37: Figure 3B; (2) more unfair to harm a female, paired samples t-test: t(49) 1⁄4 5.03, p < .001, Cohen’s d 1⁄4 .34: Figure 3C; and men have a significantly greater tolerance to pain, paired samples t-test: t(49) 1⁄4 4.1, p < .001, Cohen’s d 1⁄4 .98: Figure 3D

They also found that people believed that men have a greater tolerance to pain (this is not true, but belief that a group has greater tolerance to pain is known to increase willingness to inflict pain on them)

They concluded that male disposability is the result of social acceptability:

The findings suggest that social norms regarding gender and harm considerations likely account for greater harming behavior toward a male than a female target. Moreover, there are widely held societal perceptions that females are less tolerant to pain, that it is unacceptable to harm females for personal gain, and that society endorses chivalrous behavior. … that society perceives harming women as more morally unacceptable, suggests that gender bias and harm considerations play a large role in shaping moral action.

Overall they found that that people treat men significantly worse than women under the same conditions.

participants overwhelming responded that they would push a man— rather than a woman—in front of an oncoming trolley. When we tested this effect in a different class of moral challenge where self-benefit and another’s welfare are juxtaposed, we found that even under the same moral constraints where all components of the moral task were held constant, a target’s gender can shift an individual’s choice to be more or less altruistic, providing converging evidence that gender bias plays a significant role in moral behavior.

Feminism, in-group bias and male disposability

To see the effect of social attitudes on male disposability, we can examine how people’s beliefs about gender alters their behaviour

A study

[5]

conducted by the University of Exeter tested the reaction of women who identified as feminists, and those who did not, to the moral choice dilemma.

The task consists of eight short scenarios in which sacrificing one person can save a number of others. In each scenario, the gender of the protagonist is manipulated: In four scenarios, participants are asked to sacrifice a man to save several others (of unspecified gender), and in four other scenarios they are asked to sacrifice a woman. The scenarios in which men and women appeared were counterbalanced across participants.In each scenario, participants indicate whether they would sacrifice the protagonist by answering the Yes/No question, “Would you sacrifice this man [woman] to save the others?” Willingness to sacrifice was computed by summing the number of scenarios in which participants sacrificed the target individual. As such, the willingness to sacrifice in the MCD task can show evidence for in-group favoritism and/or out-group derogation.For instance, increased tendencies to sacrifice out-group members (men) would be indicative of out-group derogation (Brewer, 1999).We believe that the use of the MCD task as a measure of in-group bias has several benefits. First, the MCD task is an indirect measure, in which participants are not made aware of the role played by gender. In the context of the current study, we consider this to be an important benefit, as it ensures that the gender component is not referred to explicitly until the very end of the procedure and any effects of the subliminal manipulation are not altered by explicit reference to gender. Second, avoiding explicit reference to gender means that participants’ responses are less likely to be affected by conscious correction of gender bias.

van Breen said her team’s research is the first to show that feminists are more willing to sacrifice men, though previous studies have found similar results with other marginalized groups, such as racial minorities.“If a person wanted to counteract that and ‘level the playing field’, that can be done either by boosting women or by downgrading men” van Breen told Campus Reform. “So I think that this effect on evaluations of men arises because our participants are trying to achieve an underlying aim: counteracting gender stereotypes.”

Where do these attitudes come from?

Social attitudes can come from multiple sources, however one major influence is socialisation by parents.

A study conducted by researchers at the University of Guelph suggests mothers treat boys and girls differently, while fathers treat them the same

[6]

.

Nearly 600 Canadian and American parents were shown images of children between the ages of eight and 12 conveying sadness, anger, or neutral expressions as part of the study. Participants were then told to sort each image into a “pleasant” or “unpleasant” category.

The results showed that mothers were more likely to categorise boys as “unpleasant” than girls showing the same behaviour. However fathers regarded both boys and girls the same.

“Moms actually think that girls expressing anger is more pleasant or more acceptable than boys expressing anger,” Prof. Thomassin said.

Conclusion

The research consistently shows that men are treated as less valuable, that people are more willing to inflict violence or harm on men than women, that harm to men is seen as less serious than harm to women, and that people are more willing to help women than men. In addition the research shows that women discriminate against men more than men do.

Male disposability is most likely enforced by social norms, and children are socialised to male disposability by mothers, but not by fathers.

Updates

2020-07-06: Added cycling study

Citations

1.

FeldmanHall, Oriel and Dalgleish, Tim and Evans, Davy and Navrady, Lauren and Tedeschi, Ellen and Mobbs, Dean, Moral Chivalry: Gender and Harm Sensitivity Predict Costly Altruism (2016). Social Psychological and Personality Science, Vol. 7, Issue 6, 2016. ssrn.com/abstract=2896934

2.

Drivers overtaking bicyclists: Objective data on the effects of riding position, helmet use, vehicle type and apparent gender. / Walker, I. In: Accident Analysis and Prevention, Vol. 39, No. 2, 01.03.2007, p. 417-425. www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0001457506001540?via%3Dihub

3.

Gender and helping-behavior— A meta-analytic review of the social psychological literature. Psychological Bulletin, 100, 283–308

4.

Saad, G., & Gill, T. (2001). The effects of a recipient’s gender in a modified dictator game. Applied Economics Letters, 8, 463–466

5.

van Breen JA, Spears R, Kuppens T, de Lemus S. Subliminal Gender Stereotypes: Who Can Resist?. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2018;44(12):1648-1663. pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29781373/

One reply on “Male Disposability – The Evidence”

I have personally been in an altercation with a female who was the one who instigated the conflict , there were several by standers their who all witnessed the female aggressor being unnecessarily abrasive and violent towards me , but no one intervened in my defense despite witnessing me trying to maintain my composure and reluctant to fight my aggressor. Everyone stood there just watching, perhaps finding it amusing. then the female attacked me and hit me and i was about to defend myself everyone leapt to prevent me from striking her back despite witnessing that she was the aggressor who initiated the first strike.It was at that point that i realized that they weren’t trying to prevent a fight, they were there with the intention to harm me if i was to hit back the female ( despite her being the assailant) . they all stood and witnessed me ( the victim ) being harrased but did nothing but as soon as I was about to defend my self i was automatically the aggressor for being male . this gives me plausible reasons to question if all these claims of ” female domestic violence “are even true. A man can be made into the aggressor instantly when up against a female aggressor .